Environmental Justice Is Being Used to Rezone Farms

Who decides what harm looks like — and to whom?

For generations, farms expanded—or didn’t—based on tangible factors: soil, water, markets, neighbors, and basic zoning rules. Today, a quieter force is reshaping those decisions across the country. It doesn’t announce itself with a ban. It arrives as a map.

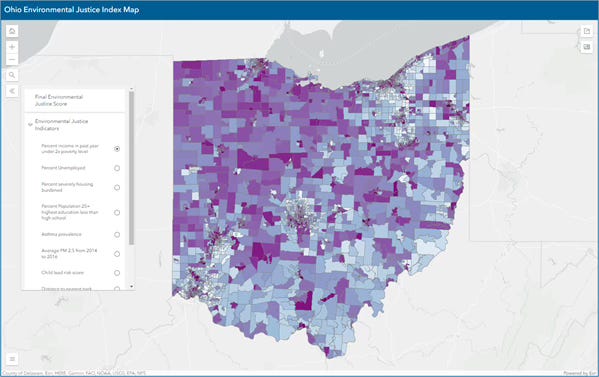

Environmental Justice (EJ) mapping tools—once designed to identify genuine pollution burdens in urban and industrial corridors—are increasingly being used by counties to halt farm expansions, deny permits, and rezone agricultural land. The justification sounds unassailable: “disproportionate impact.” The outcome, however, is increasingly clear: farms boxed in by data layers they didn’t create, can’t meaningfully challenge, and were never intended to regulate agriculture in the first place.

This isn’t speculation. It’s happening—county by county, permit by permit.

From Civil Rights Tool to Zoning Weapon

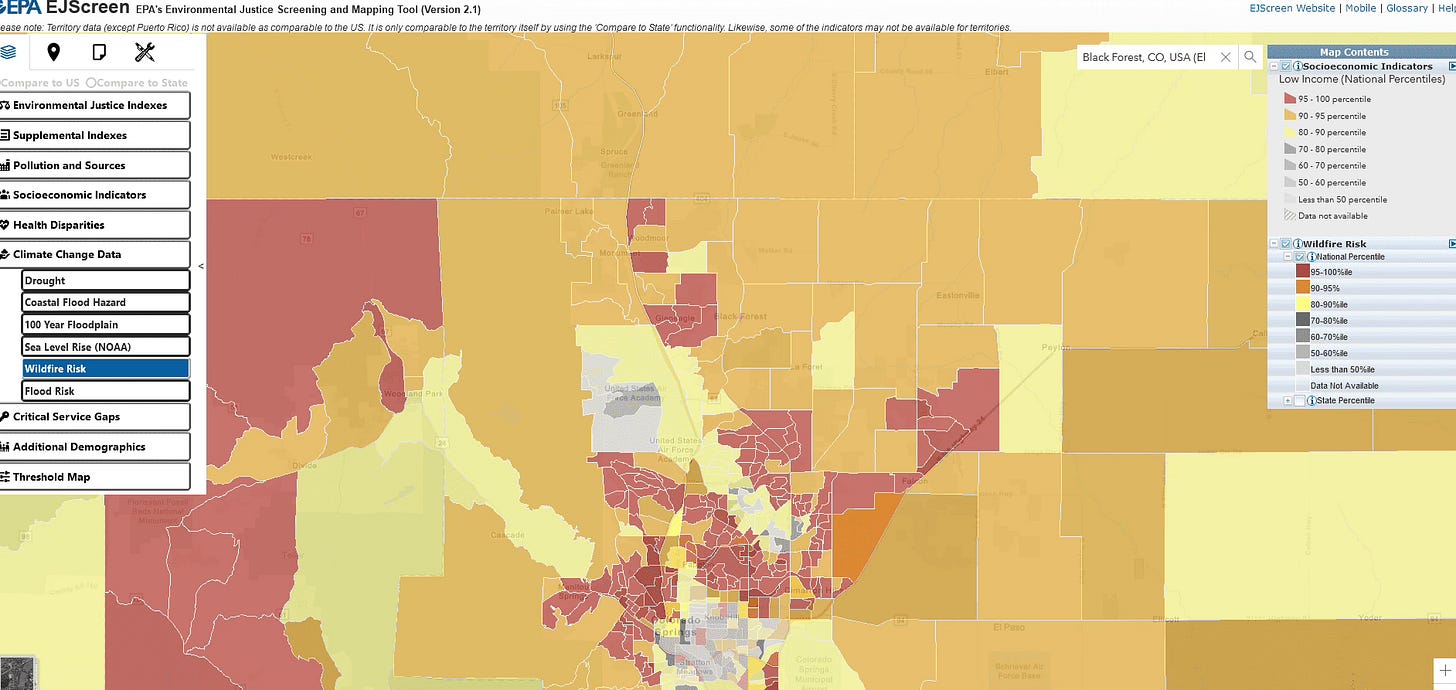

Environmental justice frameworks were created to address a real problem: historically marginalized communities bearing higher exposure to pollution from highways, refineries, landfills, and industrial sites. Tools like EJScreen—developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—combine demographic indicators with environmental data to flag areas of concern.

But these tools were built for screening, not regulation. They were designed to ask questions, not deliver verdicts.

At the county level, that distinction is being erased.

Planning boards are now overlaying EJ maps onto rural landscapes and declaring proposed barns, dairies, feedlots, compost facilities, processing plants—even greenhouses—as “new sources of disproportionate impact.” In many cases, there is no measured pollution exceedance, no violation of existing environmental standards, and no evidence of actual harm.

The map alone is enough.

How the Denials Happen

The process is often bureaucratic—and devastatingly simple:

A farmer applies to expand or modernize an operation within existing agricultural zoning.

County staff run an EJ overlay, showing nearby census tracts with higher minority or low-income populations.

Officials assert “potential disproportionate impact”, even when the activity is explicitly permitted under agricultural use.

Permits are delayed, conditioned, or denied, citing EJ obligations or the risk of future litigation.

Critically, the farmer is rarely accused of causing harm. Instead, they are told the risk of perception is too high.

The burden shifts: not “prove you meet the law,” but “prove no one could ever feel impacted.”

Agriculture Is Not Industry — But It’s Being Treated Like One

EJ mapping does not distinguish between a family dairy and a petrochemical facility. It measures proximity, demographics, and modeled risk—not land-use context or historic compatibility.

In practice, that means:

A manure lagoon is treated like a waste dump.

A livestock barn is treated like a factory.

A farm road is treated like a freight corridor.

This flattening of context is especially dangerous in rural areas where agricultural operations predate surrounding development—often by decades or centuries. When residential growth pushes outward, farms don’t move. The map changes around them.

Suddenly, the farm is framed as the intruder.

The Quiet Rezoning Effect

Few counties openly say they are rezoning farms out of existence. They don’t have to.

By stacking EJ-based conditions—air modeling, odor mitigation plans, traffic studies, buffer expansions—projects become financially impossible. Lenders walk. Younger generations reconsider succession. Expansion dies on the vine.

Land that was once viable for production becomes “nonconforming by default.”

Developers, however, face a different path. Housing proposals are often approved with mitigations, offsets, or phased buildouts—because housing is framed as a social good. Agriculture, increasingly, is framed as a risk.

The result is a perverse outcome: farms are frozen while subdivisions march forward.

Who Decides What Harm Looks Like?

This is the question at the heart of the issue.

EJ determinations are often made without:

On-site monitoring

Longitudinal health data

Comparison to baseline agricultural activity

Consideration of existing Right-to-Farm protections

Instead, decisions rely on proxy indicators and hypothetical exposure pathways. Harm becomes a prediction, not a measurement.

And predictions are political.

County attorneys openly acknowledge the fear: deny the permit now, avoid the lawsuit later. Environmental justice becomes less about protecting communities and more about institutional risk management.

Farmers are collateral.

The Irony: Food Deserts and Forced Imports

Many of the same EJ maps used to block farm expansion also flag areas as food deserts.

The contradiction is stark.

Local farms that could increase production, add processing, or shorten supply chains are prevented from doing so—while those same communities remain dependent on food trucked in from hundreds or thousands of miles away.

Environmental justice, in practice, is being used to externalize food production to places—and people—who don’t appear on the map.

Legal Ground Is Shifting

Right-to-Farm laws were designed to protect agriculture from nuisance claims and encroachment. EJ frameworks now sidestep those protections by reframing disputes as civil rights or environmental equity issues rather than land-use conflicts.

This legal gray zone favors regulators. Farmers face mounting costs to challenge denials, often without clear appeal standards because EJ “considerations” are discretionary.

Once again, no ban is necessary. Delay does the work.

What This Means for the Future of Farming

If this trajectory continues, the implications are profound:

Farm consolidation accelerates, as only the largest operations can absorb regulatory uncertainty.

Mid-size family farms stall, unable to expand or adapt.

Rural land use tilts toward residential and recreational development, not production.

Food systems grow more centralized, not more resilient.

All under the banner of justice.

Justice for Whom?

Environmental justice matters. Communities should not be poisoned, ignored, or sacrificed for economic gain.

But when EJ tools are used to quietly rezone farms—without evidence, without proportionality, and without acknowledging agriculture’s role in food security—they stop being instruments of justice and start becoming instruments of displacement.

The question isn’t whether justice matters.

It’s whether justice that erases farmers, fractures food systems, and treats production itself as harm is justice at all.